Pap test

The Papanicolau test (also called Pap smear, Pap test, cervical smear, or smear test) is a screening test used in gynecology to detect premalignant and malignant (cancerous) processes in the ectocervix. Significant changes can be treated, thus preventing cervical cancer. The test was invented by and named after the prominent Greek doctor Georgios Papanikolaou. An anal Pap smear is an adaptation of the procedure to screen and detect anal cancers.

In taking a Pap smear, a tool is used to gather cells from the outer opening of the cervix (Latin for "neck") of the uterus and the endocervix. The cells are examined under a microscope to look for abnormalities. The test aims to detect potentially pre-cancerous changes (called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or cervical dysplasia), which are usually caused by sexually transmitted human papillomaviruses (HPVs). The test remains an effective, widely used method for early detection of pre-cancer and cervical cancer. The test may also detect infections and abnormalities in the endocervix and endometrium.

In general, it is recommended that females who have had sex seek regular Pap smear testing. Guidelines on frequency vary, from annually to every three years.[1][2] If results are abnormal, and depending on the nature of the abnormality, the test may need to be repeated in six to twelve months.[3] If the abnormality requires closer scrutiny, the patient may be referred for detailed inspection of the cervix by colposcopy. The patient may also be referred for HPV DNA testing, which can serve as an adjunct to Pap testing.

Contents |

Whom to screen

Guidelines on whom to screen vary from country to country. In general, screening starts at age 20 or 25 and continues until about age 50 or 60.[4] There is probably no benefit screening women aged 60 or over whose previous tests have been negative.[5]

There is little or no benefit to screening women who have not had sexual contact. HPV can be transmitted in sex between women, so women who have only had sex with other women should be screened, although they are at somewhat lower risk for cervical cancer.[6]

Guidelines on frequency of screening vary—typically every one to three years for those who have not had previous abnormal smears. Women should wait no more than three years after the first time they have intercourse to start screening since most women contract HPV soon after becoming sexually active.[2] It takes an average of a year, but can take up to four years, for a woman's immune system to control the initial infection. Screening during this period may show this immune reaction and repair as mild abnormalities, which are usually not associated with cervical cancer, but could cause the woman stress and result in further tests and possible treatment. Cervical cancer usually takes time to develop, so delaying the start of screening a few years does not pose much risk of missing a potentially precancerous lesion.

Pap smear screening is still recommended for those who have been vaccinated against HPV, since the vaccines do not cover all of the HPV types that can cause cervical cancer. Also, the vaccine does not protect against HPV exposure before vaccination.

Procedure

For best results, a Pap test should not occur when a woman is menstruating. However, Pap smears can be performed during a woman's menstrual period, especially if the physician is using a liquid-based test; if bleeding is extremely heavy, endometrial cells can obscure cervical cells, and it is therefore inadvisable to have a Pap smear if bleeding is excessive.

The patient's perception of the procedure ranges from no discomfort at all to severe discomfort (especially in women with cervical stenosis). Many women experience spotting or mild cramping afterward.

The physician or operator collecting a sample for the test inserts a speculum into the patient's vagina, to allow access to the cervix. Samples are collected from the outer opening or os of the cervix using an Aylesbury spatula and an endocervical brush, or (more frequently with the advent of liquid-based cytology) a plastic-fronded broom. The broom is not as good a collection device, since it is much less effective at collecting endocervical material than the spatula and brush.[7] The cells are placed on a glass slide and checked for abnormalities in the laboratory.

The sample is stained using the Papanicolaou technique, in which tinctorial dyes and acids are selectively retained by cells. Unstained cells cannot be visualized with light microscopy. The stains chosen by Papanicolaou were selected to highlight cytoplasmic keratinization, which actually has almost nothing to do with the nuclear features used to make diagnoses now.

In some cases, a computer system may pre-screen the slides, indicating some that do not need examination by a person, or highlighting areas for special attention. The sample is then usually screened by a specially trained and qualified cytotechnologist using a light microscope. The terminology for who screens the sample varies according to the country; in the UK, the personnel are known as Cytoscreeners, Biomedical scientists (BMS), Advanced Practitioners and Pathologists. The latter two take responsibility for reporting the abnormal sample which may require further investigation.

Results

In screening a general or low-risk population, most Pap results are normal.

In the United States, about 2-3 million abnormal Pap smear results are found each year.[8] Most abnormal results are mildly abnormal (ASC-US (typically 2-5% of Pap results) or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) (about 2% of results)), indicating HPV infection. Although most low-grade cervical dysplasias spontaneously regress without ever leading to cervical cancer, dysplasia can serve as an indication that increased vigilance is needed.

In a typical scenario, about 0.5% of Pap results are high-grade SIL (HSIL), and less than 0.5% of results indicate cancer; 0.2 to 0.8% of results indicate Atypical Glandular Cells of Undetermined Significance (AGC-NOS).

As liquid based preparations (LBPs) become a common median for testing, atypical result rates have increased. The median rate for all preparations with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions using LBPs was 2.9% compared with a 2003 median rate of 2.1%. Rates for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (median, 0.5%) and atypical squamous cells have changed little.[9]

Abnormal results are reported according to the Bethesda system. They include:

- Squamous cell abnormalities (SIL)

- Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

- Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LGSIL or LSIL)

- Atypical squamous cells - cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H)

- High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL or HSIL)

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Glandular epithelial cell abnormalities

- Atypical Glandular Cells not otherwise specified (AGC or AGC-NOS)

Endocervical and endometrial abnormalities can also be detected, as can a number of infectious processes, including yeast, herpes simplex virus and trichomoniasis.

Other Options

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has funded an eight-year study of a DNA test for the virus that causes cervical cancer. The test manufactured by Qiagen for a low cost per test with results available in only a few hours may allow reduction in use of annual pap exams. The test has been shown to work "acceptably well" on women that take the swabs themselves rather than allowing a physician to test. This may allow women that are unwilling to be screened due to discomfort or modesty.[10]

Effectiveness

Prior to the introduction of the Pap test, carcinoma of the cervix was a leading cause of cancer death in women. Since the introduction of the Pap test, deaths caused by carcinoma of the cervix have been reduced by up to 99% in some populations wherein women are screened regularly.[11]

Failure of prevention of cancer by the Pap test can occur for many reasons, including not getting regular screening, lack of appropriate follow up of abnormal results, and sampling and interpretation errors.[11] In the US, over half of all invasive cancers occur in women that have never had a Pap smear; an additional 10 to 20% of cancers occur in women that have not had a Pap smear in the preceding five years. About one-quarter of US cervical cancers were in women that had an abnormal Pap smear, but did not get appropriate follow-up (woman did not return for care, or clinician did not perform recommended tests or treatment).

Adenocarcinoma of the cervix has not been shown to be prevented by Pap tests.[11] In the UK, which has a Pap smear screening program, Adenocarcinoma accounts for about 15% of all cervical cancers[12]

Estimates of the effectiveness of the United Kingdom's call and recall system vary widely, but it may prevent about 700 deaths per year in the UK. A medical practitioner performing 200 tests each year would prevent a death once in 38 years, while seeing 152 women with abnormal results, referring 79 for investigation, obtaining 53 abnormal biopsy results, and seeing 17 persisting abnormalities lasting longer than two years. At least one woman during the 38 years would die from cervical cancer despite being screened.[13]

Since the population of the UK is about 61 million, the maximum number of women who could be receiving Pap smears in the UK is around 15 million to 20 million (eliminating the percentage of the population under 20 and over 65). This would indicate that the use of Pap smear screening in the UK saves the life of 1 person for every approximately 20,000 people tested (assuming 15,000,000 are being tested yearly). If only 10,000,000 are actually tested each year, then it would save the life of 1 person for every approximately 15,000 people tested.

Technical aspects

Conventional cytology

In the conventional Pap smear, the physician collecting the cells smears them on a microscope slide and applies a fixative. In general, the slide is sent to a laboratory for evaluation.

Studies of the accuracy of conventional cytology report:[14]

- sensitivity 72%

- specificity 94%

Liquid-based monolayer cytology

Since the mid-1990s, techniques based on placing the sample into a vial containing a liquid medium that preserves the cells have been increasingly used. The media are primarily ethanol-based for Sure-Path and methanol for ThinPrep. Two of the types are Sure-Path (TriPath Imaging) and Thin-Prep (Cytyc Corp). Once placed into the vial, the sample is processed at the laboratory into a cell thin-layer, stained, and examined by light microscopy. The liquid sample has the advantage of being suitable for low- and high-risk HPV testing and reduced unsatisfactory specimens from 4.1% to 2.6%.[15] Proper sample acquisition is crucial to the accuracy of the test; therefore, a cell that is not in the sample cannot be evaluated.

Studies of the accuracy of liquid based monolayer cytology report:

Some[15], but not all studies[14][16], report increased sensitivity from the liquid-based smears.

Human papillomavirus testing

The presence of HPV indicates that the person has been infected; the majority of women that get infected will successfully clear the infection within 18 months. It is those that have an infection of prolonged duration with high-risk types[17] (e.g. types 16,18,31,45) that are more likely to develop Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia due to the effects that HPV has on DNA. Studies of the accuracy of HPV testing report:

- sensitivity 88% to 91% (for detecting CIN 3 or higher)[16] to 97% (for detecting CIN2+)[18]

- specificity 73% to 79% (for detecting CIN 3 or higher)[16] to 93% (for detecting CIN2+)[18]

By adding the more sensitive HPV Test, the specificity may decline. However, the drop in specificity is not definite.[19] If the specificity does decline, the result is increased numbers of false positive tests and, for many women that did not have disease, an increased risk for colposcopy[20] and treatment. A worthwhile screening test requires a balance between the sensitivity and specificity to ensure that those having a disease are correctly identified as having it and those without the disease are not identified as having it. Due to the liquid based pap smears' having a false negative rate of 15-35%, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology[21] have recommended the use of HPV testing in addition to the pap smear in all women over the age of 30.

Regarding the role of HPV testing, randomized controlled trials have compared HPV to colposcopy. HPV testing appears as sensitive as immediate colposcopy while reducing the number of colposcopies needed.[22] Randomized controlled trial have suggested that HPV testing could follow abnormal cytology[16] or could precede cervical cytology examination.[18]

A study published in April 2007 suggested that the act of performing a Pap smear produces an inflammatory cytokine response, which may initiate immunologic clearance of HPV, therefore reducing the risk of cervical cancer. Women that had even a single Pap smear in their history had a lower incidence of cancer. "A statistically significant decline in the HPV positivity rate correlated with the lifetime number of Pap smears received."[23]

Automated analysis

In the last decade, there have been successful attempts to develop automated, computer image analysis systems for screening.[24] Although, on the available evidence automated cervical screening could not be recommended for implementation into a national screening program, a recent NHS Health technology appraisal concluded that the 'general case for automated image analysis ha(d) probably been made'[25] . Automation may improve sensitivity and reduce unsatisfactory specimens.[26] Two of these has been FDA approved and functions in high volume reference laboratories, with human oversight.

Practical aspects

The endocervix may be partially sampled with the device used to obtain the ectocervical sample, but, due to the anatomy of this area, consistent and reliable sampling cannot be guaranteed. As abnormal endocervical cells may be sampled, those examining them are taught to recognize them.

The endometrium is not directly sampled with the device used to sample the ectocervix. Cells may exfoliate onto the cervix and be collected from there, so as with endocervical cells, abnormal cells can be recognised if present but the Pap Test should not be used as a screening tool for endometrial malignancy.

Gallery

Endocervical adenocarcinoma on a pap test. |

Candida organisms on a pap test. |

Viral cytopathic effect consistent with herpes simplex virus on a pap test. |

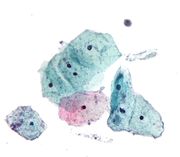

Normal squamous epithelial cells in premenopausal women |

Atrophic squamous cells in postmenopausal women |

|

Normal endocervical cells should be present into the slide, as a proof of a good quality sampling |

the cytoplasms of squamous epithelial cells melted out; many Döderlein bacilli can be seen |

Infestation by Trichomonas vaginalis |

An obviously atypical cell can be seen |

References

- Notes

- ↑ U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2003). Screening for Cervical Cancer: Recommendations and Rationale. AHRQ Publication No. 03-515A. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 American Cancer Society. (2010). Detailed Guide: Cervical Cancer. Can Cervical Cancer Be Prevented? Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ↑ The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2009). ACOG Education Pamphlet AP085 -- The Pap Test. Washington, DC. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ↑ Strander B (2009). "At what age should cervical screening stop?". Brit Med J 338: 1022–23. doi:10.1136/bmj.b809.

- ↑ Saiseni P, Adams J, Cuzick J (2003). "Benefit of cervical screening at different ages: evidence from the UK audit of screening histories". Br J Cancer 89 (1): 88–93. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600974. PMID 12838306.

- ↑ Marrazzo, JM; et al. (2001). "Papanicolaou Test Screening and Prevalence of Genital Human Papillomavirus Among Women who have Sex with Women". American Journal of Public Health 91 (6): 947–952. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.6.947. PMID 11392939.

- ↑ Martin-Hirsch P, Lilford R, Jarvis G, Kitchener HC. (1999). "Efficacy of cervical-smear collection devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet 354 (9192): 1763–1770. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02353-3. PMID 10577637.

- ↑ "Pap Smear". http://www.emedicinehealth.com/pap_smear/article_em.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20196659

- ↑ McNeil Jr, Donald G. (2009-04-07). "DNA Test Outperforms Pap Smear". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/07/health/07virus.html?_r=2&em. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 DeMay, M. (2007). Practical principles of cytopathology. Revised edition.. Chicago, IL: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press. ISBN 978-0-89189-549-7.

- ↑ "Cancer Research UK website". http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/cervix/incidence/. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ Raffle AE, Alden B, Quinn M, Babb PJ, Brett MT (2003). "Outcomes of screening to prevent cancer: analysis of cumulative incidence of cervical abnormality and modeling of cases and deaths prevented". BMJ 326 (7395): 901. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7395.901. PMID 12714468.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Coste J, Cochand-Priollet B, de Cremoux P, et al. (2003). "Cross sectional study of conventional cervical smear, monolayer cytology, and human papillomavirus DNA testing for cervical cancer screening". BMJ 326 (7392): 733. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7392.733. PMID 12676841. ACP Journal Club

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ronco G, Cuzick J, Pierotti P, et al. (2007). "Accuracy of liquid based versus conventional cytology: overall results of new technologies for cervical cancer screening randomised controlled trial". BMJ 335 (7609): 28. doi:10.1136/bmj.39196.740995.BE. PMID 17517761.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Kulasingam SL, Hughes JP, Kiviat NB, et al. (2002). "Evaluation of human papillomavirus testing in primary screening for cervical abnormalities: comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and frequency of referral". JAMA 288 (14): 1749–57. doi:10.1001/jama.288.14.1749. PMID 12365959.

- ↑ Cuschieri KS, Cubie HA, Whitley MW, et al. (2005). "Persistent high risk HPV infection associated with development of cervical neoplasia in a prospective population study". J. Clin. Pathol. 58 (9): 946–50. doi:10.1136/jcp.2004.022863. PMID 16126875.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Cuzick J, Szarewski A, Cubie H, et al. (2003). "Management of women who test positive for high-risk types of human papillomavirus: the HART study". Lancet 362 (9399): 1871–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14955-0. PMID 14667741.

- ↑ Arbyn M, Buntinx F, Van Ranst M, Paraskevaidis E, Martin-Hirsch P, Dillner J (2004). "Virologic versus cytologic triage of women with equivocal Pap smears: a meta-analysis of the accuracy to detect high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 96 (4): 280–93. doi:10.1093/jnci/djh037. PMID 14970277.

- ↑ Colposcopy and Treatment of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Beginner's Manual

- ↑ Wright TC, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB, Wilkinson EJ (2002). "2001 Consensus Guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities". JAMA 287 (16): 2120–9. doi:10.1001/jama.287.16.2120. PMID 11966387.

- ↑ ASCUS-LSIL Traige Study (ALTS) Group. (2003). "Results of a randomized trial on the management of cytology interpretations of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 188 (6): 1383–92. PMID 12824967.

- ↑ [1], J Inflamm 2007;4.

- ↑ Biscotti CV, Dawson AE, Dziura B, et al. (2005). "Assisted primary screening using the automated ThinPrep Imaging System". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 123 (2): 281–7. doi:10.1309/AGB1MJ9H5N43MEGX. PMID 15842055.

- ↑ Willis BH, Barton P, Pearmain P, Bryan S, Hyde C, "Cervical screening programmes: can automation help? Evidence from systematic reviews, an economic analysis and a simulation modelling exercise applied to the UK". Health Technol Assess 2005 9(13).[2]

- ↑ Davey E, d'Assuncao J, Irwig L, et al. (2007). "Accuracy of reading liquid based cytology slides using the ThinPrep Imager compared with conventional cytology: prospective study". BMJ 335 (7609): 31. doi:10.1136/bmj.39219.645475.55. PMID 17604301.

External links

- Obtaining Pap Smear Video

- Jo's Trust - UK's leading cervical cancer charity.

- Imaginis - Pap Smear information

- International Agency for Research on Cancer - Resource about screening, including that of Cervical Cancer. There are digital atlases of coloscopy, histology and cytology, the rationale of screening and setting up of a screening programme.

- The Pap Test: Questions and Answers — National Cancer Institute — from the U.S.'s National Cancer Institute

- Pap Smear — from eMedicineHealth

- MedlinePlus: Cervical Cancer Prevention/Screening — from MedlinePlus

- The Bethesda 2001 Workshop, held April 30 - May 2, 2001, reviewed issues regarding terminology and reporting of cervical cytology

- NCI Bethesda System Web Atlas, with 349 images of different Pap smear morphologic findings — from the American Society of Cytopathology

- Canadian Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Screening - Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada

- The UK's National Association of Cytologists

- British Society for Clinical Cytology

- IBMS — The Institute of Biomedical Science on cellular pathology

- NHS Cervical Screening Programme — from the UK's National Health Service

- EngenderHealth- Cervical Cancer Screening

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||